Atop the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in London’s Piccadilly Circus stands a statue of a beautiful young man, balancing on his left foot and firing an imaginary arrow originally aimed toward the Houses of Parliament. Don’t let the wings, nudity, and archery gear fool you. Contrary to more than a century of common belief, this fine specimen of bronze and alumin(i)um is not a statue of Cupid.

Cupid (or Eros, to the Greeks) was the god of romantic and sexual desire. His quiver was filled with a mixture of golden arrows, used to arouse uncontrollable attraction and longing, and leaded arrows to inspire deepest loathing. As with most other Greek gods, consent didn’t feature high on Eros’s list of priorities. He took aim at whichever unsuspecting target he pleased, more intent on causing emotional mayhem through forced, one-sided obsessions and aversions than on actual matchmaking. Not even other gods were exempt from his trickery.

By the 4th century BCE, the Greeks had started to dilute some of Eros’s power by depicting him not as an intimidatingly attractive adult, but rather as a young, impishly playful child. No longer acting independently, Eros was now said to simply be carrying out the whims of his mother, Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty. In one Greek legend, even she grew tired of Eros’s brattiness and asked Themis, goddess of justice and divine law, for advice on how to help him grow past his perpetual childhood.

Themis suggested that Eros was lonely and needed a sibling to balance him and help him mature. Themis’s reasoning was that “love must be answered if it is to prosper.”

Enter Anteros, Greek god of returned, reciprocal love.

Unlike his brother, Anteros has always been depicted as a grown man. His leaden arrows avenge those who have been scorned or mistreated in love and punish those who use love to manipulate or cause harm. He also has a golden club, for times when a more, shall we say, blunt approach is necessary.

Both Eros and Anteros are said to be fathered by Ares, the god of war. An alternate origin story for Anteros is that he arose from the mutual same-sex love between Poseidon and the minor sea deity Nerites, brother to the Nereid nymphs of the Aegean Sea. (Spoiler alert: Greek mythology is hella queer when it’s not too busy being misogynistic). In either case, Anteros functioned as both antidote and complement to Eros, counteracting his mischief and helping to bring about healthy, mutual love between true partners.

When the Roman ruling classes co-opted the Greek gods in the 2nd century BCE, Aphrodite became Venus and Eros became Cupid. Anteros was omitted from the pantheon and did not receive a Roman counterpart identity. Cupid was romantically paired with the mortal princess Psyche, and Anteros pretty much disappeared from popular culture.

Well, that is until some Dead White European Dudes decided to make him into a public art installation.

“The Angel of Christian Charity”

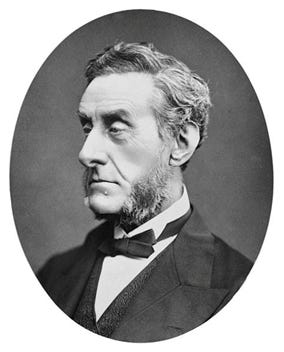

The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury was known to his family as Anthony Ashley-Cooper and to working-class Victorian Brits as “The Poor Man’s Earl.” During his time serving in various Parliamentary committees, Shaftesbury pushed through a series of laws that led to better treatment of patients in mental health asylums, banned women and children from working in coal mines, and limited the maximum number of hours that children and teenagers could work in textile factories. Shaftesbury also authored the Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act 1864, which banned chimney sweeps from employing children under the age of 10, and requiring that no one under age 16 was to be present while chimneys were being swept.

Shaftesbury called upon his strong evangelical Christian faith as motivation for his political and social advocacy on behalf of England’s poor and working classes. Unfortunately, his Zionism informed his foreign policy stances, prompting him to support British colonization in Palestine and Syria and the Anglican Church’s missionary efforts to convert Jewish people to Christianity.

Prior to his death in 1885, Shaftesbury had expressed his desire for a quiet burial on the grounds of his estate at Wimborne St. Giles in East Dorset. That wish was granted, but not until after his coffin was paraded through the streets on its way to an elaborate public funeral service at Westminster Abbey. Shaftesbury was eulogized by Charles Spurgeon, a Reformed Baptist preacher who was something akin to the Billy Graham of his era. Sir George Williams, founder of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), chaired the organizing committee for Shaftesbury’s funeral and served as one of the pallbearers.

Within 16 days of his death, the Shaftesbury Memorial Committee decided that in addition to a marble statue of his likeness to be placed in Westminster Abbey, the late Earl should also be memorialized by a work “in bronze, the pedestal of which should record in bas relief Lord Shaftesbury's principal labours, should be erected on a conspicuous site in one of the most frequented public thoroughfares in London.” English sculptor Sir Alfred Gilbert chose to create a statue-topped water fountain to be named The God of Selfless Love, appropriating the Greek god’s true meaning as a way of honoring Shaftesbury’s philanthropic legacy. Gilbert felt Anteros symbolized “reflective and mature love, as opposed to Eros or Cupid, the frivolous tyrant.”

After years of delays caused by site selection snafus, prolonged (and often heated) debate over the size and design of the structure’s base, and miscommunications over material sourcing leading to significant out-of-pocket costs to the artist, the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain was finally unveiled on June 29, 1893. The Magazine of Art praised Gilbert’s work as:

“a striking contrast to the dull ugliness of the generality of our street sculpture…a work which, while beautifying one of our hitherto desolate open spaces, should do much towards the elevation of public taste in the direction of decorative sculpture.”

Unfortunately, a good many members of said public absolutely hated it.

Despite considerable tweaking after the unveiling, the water feature never did create the “glassy dome” of water surrounding the statue that Gilbert intended. Overspray from the upper water jets frequently splashed people standing near the fountain’s lower basin. The ground around the fountain’s too-small base stayed constantly muddy and littered with trash. The eight drinking cups were stolen almost immediately, and the structure itself was repeatedly vandalized.

Added to the practical complaints was the inevitable moral pearl-clutching. The statue’s adult nudity was shocking and its Greek roots far too “pagan” for many Victorians’ tastes. Piccadilly Circus was also in the center of the West End’s theater, nightclub, (and prostitution) district. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would have discreetly called the area “bohemian.” Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas would have called it “Saturday night.” Such an unseemly location was surely inappropriate for a tribute to a man as socially respectable and deeply religious as the late Shaftesbury.

The statue was rebranded as The Angel of Christian Charity as an effort to appease the morality police, but the name never really stuck. The public had already firmly decided the figure was neither angel nor Christian, and the only god they saw atop the fountain was Eros. Over a century later, London’s most famous statue is still best known by the name its creator specifically wished to avoid, even by the daily newspaper that uses its likeness as its business logo.

The Love That Dares to Speak its True Name

Someday, I want to visit Piccadilly Circus. I want to get up before sunrise, go stand at the foot of the Shaftesbury Memorial, and consider its contradictions.

I’ll think about an earl born into generational wealth to absent, neglectful parents in a loveless marriage. I’ll reflect on how both the man himself and the monument built to honor his legacy were inconsistently composed, inherently flawed, and created considerable burdens along with their benefits.

I’ll ponder the decision to honor a deeply religious man with a graven image of a deity outside his faith, a nude figure clad in nothing but an appropriated name and the suggestion of draped cloth, a memorial to lifelong charity placed smack-dab in the middle of a global hive of conspicuous consumption.

I might compare how forthright the ancient Greeks were about the fickleness of their gods with how much Christians just like to call theirs ineffable and say He works in mysterious ways.

But mainly, I’ll be thankful that nothing about a romantic relationship that’s now lasted nearly half my lifetime has involved being manipulated by an impulsive, immortal puppeteer.

Dear Spouse and I could have gotten married on Valentine’s Day in a frock coat and a chapel veil in a church full of flowers and organ music. We could have filled a guest list with a bunch of relatives we barely tolerated, a bunch of acquaintances we hardly knew, and spent way too much money on trying to impress everyone. We could have filled a wedding registry with expensive gift requests, a reception hall with winged paper cherubs, and made our bridesmaids wear pink.

Both of us would rather eat glass.

Instead, we got married on February 19th in the law library of the county courthouse on a Tuesday afternoon. I wore a pantsuit as we exchanged vows in front of a Notary Public and two witnesses. Nobody wore white. Our reception consisted of dinner reservations at our favorite restaurant and a 6” mini cake from the local grocery store bakery decorated with three frosting flowers and zero plastic figurines. Our bespoke braided gold Celtic wedding bands were our only extravagance, and they didn’t arrive from the jeweler in Scotland until two days after the wedding. The rings we used during the ceremony belonged to Dear Spouse’s parents, which my mother-in-law loaned to us temporarily as a token of her blessing.

We picked our nondescript wedding date precisely because it was an otherwise ordinary day made extraordinary by the meaning we chose to give it. We didn’t want the “Hallmark holiday” associations or any more socially enforced heteronormativity than we could possibly avoid. We were entering into a lifelong mutual romantic partnership, not solidifying a political alliance or dodging Grandpappy’s shotgun.

We know what our marriage looks like in many ways to those outside of it. We know the assumptions they make about it, the labels they try to force onto it, and what “truths” they think it proves about us.

We know that love is patient, kind, and does not envy or dishonor. We also know that love is not one-directional, manipulative, possessive, or obsessive. We know love comes in many forms and none of them can be compelled. We know that love picks partners, not sides, and that relationships don’t have to look or function in any one certain way to be real, true, and healthy.

Ironically, February 19th is also the date in 356 A.D. that Emperor Constantius II banned the worship of pagan idols in the Roman Empire under penalty of death.

Maybe on some future anniversary date, I’ll get to look up at Anteros in person and say, just to myself: “I see you up there. I know they put you in a place that wasn’t designed for you to comfortably fit. I know what they assume when they look at you. I know the jokes, the rumors, and the lies they tell about you. I know what they’ve decided for themselves about who you are and what you represent. I also know your real name, and I will call you by no other.”